Midwest research

Detecting soil erosion from space

A large porition of my research involves using satellite imagery and high-resolution topographic data to investigate processes that shape the Earth's surface. The use of these type of data is called "remote sensing," which is just a fancy way of saying that we make observations and measurements without actually handling physical samples. Some of my research involves using remote sensing techniques to study how modern farming practices have altered soils.

Satellite imagery (Fig. 1) of recently plowed agricultural fields shows a consistent pattern where light soils

are located on hilltops and dark soils are located in hollows (topographic lows).

Lighter materials are associated with carbon-poor soils and darker materials are

associated with soils rich with organic carbon.

We developed a new method to use measurements of color (which we call spectral reflectance)

to estimate the amount of soil organic carbon in one pixel of satellite imagery (Thaler et al., 2019).

How much topsoil has been eroded?

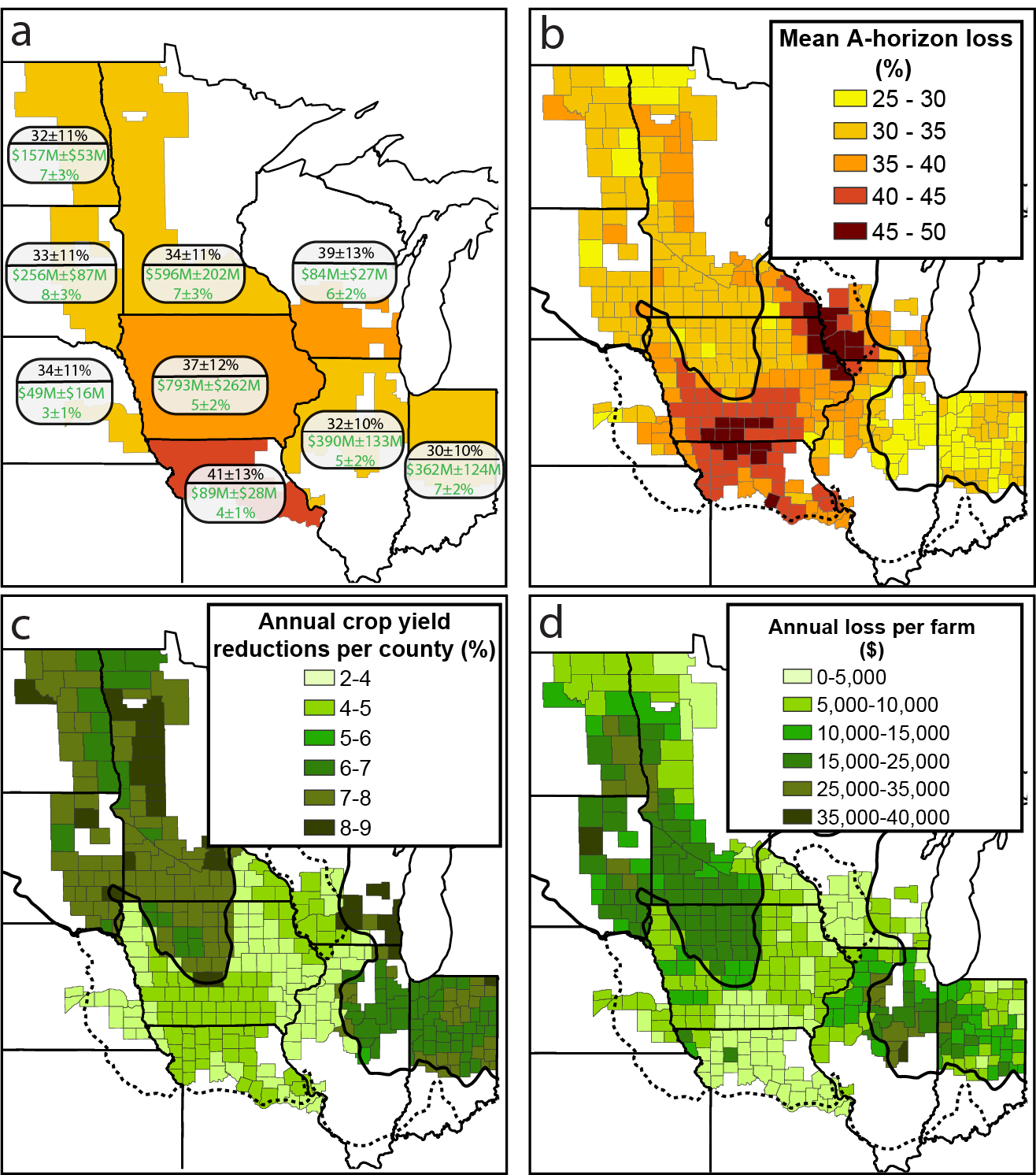

One of the main differences between topsoil (what scientists call A-horizon) and subsoil (B-horizon) is the amount of organic carbon in the soil. We used the relationship between topography (hilltops and hollows) and the satellite-derived estimate of soil organic carbon to estimate how much topsoil has been eroded across the U.S. Corn Belt (Figure 2). Erosion of that organic-rich topsoil causes crops to be less productive. When crops are less productive, farmers lose money. We made some rough estimates of the annual economic losses to farmers across the region (Thaler et al., 2021). See some of the media coverage of this work:

Field measurements of erosion

Remote sensing can help us understand the spatial extent of soil erosion, but it's pretty difficult to measure the depth of soil loss from satellite imagery alone. Prairie grasslands used to cover the midwestern US landscape, but now only a tiny fraction of these native prairies remain. Because erosion in the fields is way faster than erosion in the unfarmed prairies, soil gets removed from the fields, and right at the bounday between the prairie and the field, an erosional escarpment develops. We used a high-resolution GPS unit to measure the height of these escarpments at 20 prairies across the Corn Belt, and found that the average erosion rate across all of the sites is 1.9 mm/yr. That rate is nearly double what the U.S. Department of Agriculture considers "tolerable." You can read more about this research in our paper (Thaler et al., 2022). See some of the media coverage of this work:

What causes this erosion?

The largest fraction of the erosion on hilltops is driven by tillage erosion. When farmers prepare their fields for planting, they typically plow (AKA till) the soil. When soils on hilltops are tilled, the soil gradually gets pushed downhill, and when that tilling occurs a couple of times a year for 160 years, a lot of soil can be moved downslope.